Standing out among the crowd of youngsters displaying their new work at SPX last weekend was 71-year-old Bill Griffith, who was there signing copies of and talking about his new book Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Affair With A Famous Cartoonist (Fantagraphics). Invisible Ink is a bit of a historical detective story detailing the 16-year love affair his mother had with the then famous, but now mostly forgotten, cartoonist Lawrence Lariar, a man Griffith calls his “Shadow Father.”

Lariar was an extraordinarily prolific cartoonist whose work included comic books, newspaper strips, magazine gag panels, crime novels, several how-to-draw books, and even contributed to National Allied Publications’ (later DC) New Fun, one of the earliest 10-cent newsstand comic book to include all new material, rather than newspaper reprints. And while prolific, Lariar never achieved much success as a cartoonist himself. “He was like a comics version of Woody Allen’s Zelig character. Present at every historical moment but never a major player…” Griffith writes in Invisible Ink.

In the late 1950s, Griffith’s mother, Barbara, began working as a secretary for Lariar and would sometimes bring home work, which the young Griffith would help her with. One of her first assignment was Lariar’s recently launched annual Best Cartoons of the Year collection that reprinted gag panel cartoons from magazines as chosen by [from the inside flap of the 1954 volume]: “America’s Cartoonist-in-Chief, Lawrence Lariar.” The series ran from 1942 until 1971 and was, and Griffith says, Laiar’s “cartoon bread & butter for decades.”

Griffith’s mother had replied to an ad in New York’s Newsweek placed by Lariar looking for part-time secretary for a crime writer.

Lawrence Lariar (from Cartoon Humor Vol. 3, No. 1 March 1940)

Lawrence Lariar (from Cartoon Humor Vol. 3, No. 1 March 1940)

“It didn’t say ‘cartoonist,’” said Griffith. “My mother was a writer, she had been published a little bit, and that was what she did. He would speak his novels and she would transcribe them and then she would do all the grammar checks.” The relationship evolved over time and a good part of Invisible Ink is dedicated to Griffith’s search through history to uncover exactly who was this man his mother had been sleeping with. Barbara Griffith spoke of the affair exactly once, in 1972, moments after learning that her husband—and Griffith’s father—had been killed in a freak bicycle accident.

The book explores the effect the secret affair had on Griffith, his mother and his father. This took piecing together clues found on the internet and libraries about Lariar, who was a neighbor he hardly knew as a child growing up in Long Island, NY, and from the papers his mother left after her death in 1998, including love letters, two diaries and an unpublished novel detailing the affair. He said that he began to see Lariar as a sort of “shadow father.” While Griffith’s actual father was an intelligent man, he had no interest in art, Lariar was a “cultured intellectual.”

The Thropp Family from Liberty Magazine, May 11, 1946. Written by Lariar and drawn by Lou Fine and Don Komisarow.

The Thropp Family from Liberty Magazine, May 11, 1946. Written by Lariar and drawn by Lou Fine and Don Komisarow.

“Lariar was a New York intellectual—you’d never guess it from his comics which were strictly boffo gags, guys and gals, just low brow stuff,” Griffith said. “But Lariar introduced my mother to a whole different world of art, music and culture. They just didn’t have a ‘hot sheet’ affair. They would go to gallery shows, museums, Broadway plays, movies, and all this stuff filtered into my house through Lariar, my mother and to me. I didn’t know…I didn’t say, ‘Hey mom, how come there’s a Picasso book in the house.’ It was just there. And it was there because of him. And I poured over it and I got wrapped up in the whole world of art, and comics, both, through him. Without knowing it.”

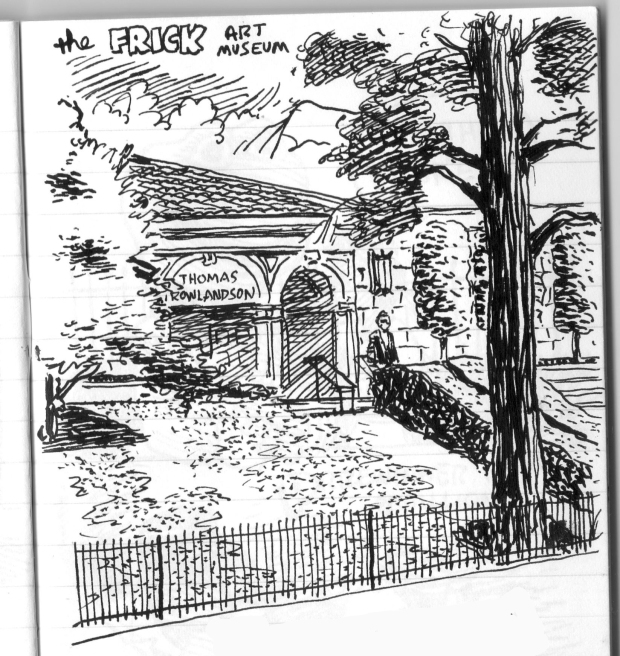

In addition to his mother’s papers, Griffith spent extensive amounts of time researching Lariar on the internet: “Go to Google and put in the name Lawrence Lariar and you will see hundreds and hundreds of pages of images, interviews, bios, articles. A huge amount of material.” He also visited the Lariar archive at Syracuse University’s library, which contains materials the artist left the school in the 1960s. Why the material is housed in Syracuse is unclear.

“I called Syracuse and asked, ‘Do you have the papers of Lawrence Larier by any chance? And they said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Has anyone ever asked for them before?’ She said, “No. You’re the first one.’ I went up there and spent a couple of days and went through boxes with white gloves and found original art, letters, scripts he wrote for early TV shows. This guy was…people think I’m prolific or overachieving? This guy was 10 times that. I can’t imagine that he had a minute to spare. He wrote 16 crime novels… He wrote three Best Selling How-to-Draw Cartoon books, one of which was in my house.”

With the help of the internet—“I can’t imagine doing this book without the internet”—Griffith then bought every single book that Lariar ever wrote, “dozens and dozens of books.”

For his mystery and crime novels, Lariar used several pseudonyms, including Michael Stark, Adam Knight and Michael Lawrence. Griffith compared them favorably to the hard-boiled style in current favor at the time and said he prefers Lariar’s crime novels to his cartooning. In addition to the Best Cartoon anthologies, Lariar served as the cartoon editor at both Parade and Liberty magazine, and he wrote or edited books—often using cartoons as illustrations—about many different topics, including golf, fishing, babies, driving, hospitals, teenagers, the suburbs and sex.

Lariar also produced several volumes of How-To-Books about cartooning, which were thoughtfully written and geared toward learning the basic skills he deemed for necessary for working cartoonists. In the mid-40s, Lariar started the Professional School of Cartooning, a correspondence school that promised to teach the art of cartooning from the likes of Henry Boltinoff, Ed Nofzinger, George Wolfe, Adolph Schus, and Lariar himself. A promise in a 1947 brochure for the School read: “Lariar’s smart, stylized cartoons are a model for many beginners, and his drawings of cute girls are familiar to all. He will criticize your drawings personally!”

Some of the most playful parts in Invisible Ink come when Griffith imagines how different his cartooning career would have turned out if he had indeed taken up Laniar’s offers to mentor him as a young artist. Griffith reimagines his Zippy strips done Laniar-style.

“There are thousands of cartoonists like Lariar we don’t know about, and in many cases for good reasons,” Griffith told comics historian Chris Mautner at a SPX. “Lariar was not somebody you’d want to sit down and read 40 or 50 years later. His crime novels hold up…but his comics…he did four daily strips. One of them ran for four years. Terrible strips, and only one of them did he draw, by the way. He wrote the others. They were done totally cynically, which is why they failed. I have all of the scripts for those materials…these were calculated make money. ‘OK, Milton Caniff has Terry and the Pirates…I’m going to do Irving and the Pirates.’ He just decided to do stuff that he thought would be popular and make money….He was after the paycheck, he was after ‘making the buck.’ And that’s what he did. He did a strip [Mr. Rumbles, drawn by Jack Sparling, another neighbor of Griffith’s] for four years where the main character was a romance writer who couldn’t get a girlfriend and so he has a Leprechaun appear to him and tell him to do stuff. And you’re reading these things and going, ‘What the Hell is going on?’ It’s much more obscure than any Underground Comic I ever remember reading. And it went on for four years.”

For Invisible Ink, Griffith chose to redraw all of Lariar’s work himself, rather than rely on reprints because “it was an instinctual felling. That’s my best way of explaining it. I wanted to feel that the book was all by my hand, every inch of it. And the idea that since I was going to refer to and show his work all throughout the book as I discovered it, if it was to be reproduced from the source—just photographed and dropped in—it would be jarring graphically. I faithfully reproduced everything of his that I put in the book. I didn’t try and make it my version of his stuff, but I felt that I had to redraw it feel like the book had a cohesive graphic feel. I also felt, I have to admit, that I was processing it in that way. That I was owning it in a way…maybe it was a bit oedipal.”

For Invisible Ink, Griffith chose to redraw all of Lariar’s work himself, rather than rely on reprints because “it was an instinctual felling. That’s my best way of explaining it. I wanted to feel that the book was all by my hand, every inch of it. And the idea that since I was going to refer to and show his work all throughout the book as I discovered it, if it was to be reproduced from the source—just photographed and dropped in—it would be jarring graphically. I faithfully reproduced everything of his that I put in the book. I didn’t try and make it my version of his stuff, but I felt that I had to redraw it feel like the book had a cohesive graphic feel. I also felt, I have to admit, that I was processing it in that way. That I was owning it in a way…maybe it was a bit oedipal.”

Invisible Ink is Griffith’s first attempt at a long-form graphic story in many years and said that writing it brought him back to his Underground Comix days when he was writing longer pieces of 10 or 12 pages rather than the routine of writing his strip Zippy, which he has produced since the 1970s and as a daily syndicated strip for the past 30 years.

Invisible Ink is Griffith’s first attempt at a long-form graphic story in many years and said that writing it brought him back to his Underground Comix days when he was writing longer pieces of 10 or 12 pages rather than the routine of writing his strip Zippy, which he has produced since the 1970s and as a daily syndicated strip for the past 30 years.

“I felt like I had been kind of damning up that urge for years,” he said. “Sometimes in Zippy I will do what amounts to a long, continuing narrative that goes on for days and days, and if you read it all together it is a long narrative, but not the way narrative feels when its done specific for the long form. In a daily strip you have to break it up. It has to feel self-contained and every four panels it has to feel like you could read it without knowing what went on before or after. Doing a long-form graphic novel is exactly like writing a novel. It requires a lot of concentration, a lot of thought about structure, continuity. I have incredible grateful feelings toward my wife Diane [Noomin] who is a really great editor. When I would bring three pages up that I did that weekend she would say, ‘You know what? I think there’s a bump between this page and the next page. I think there’s a glitch. Something is off.’ Which I didn’t see, even at this point in my career. I teach comics, and I teach kids about continuity and about how everyone does things with continuity that make presumption about the reader. You can never make presumptions in comics. You have to spell out very carefully and clearly without being didactic. It’s a tightrope walk that you have to do and you need someone with an outside view to tell you when you’ve made a glitch, when you’ve hit a bump in the continuity.”

Once he began the book, Griffith said “it just sort of flowed out,” and his routine became working on Zippy during the week and the book on the weekends.

“Luckily, Zippy kind of just rolls out of me,” he said. “Each morning I get up about 9, 9:30 and I go for a walk, about a mile, a mile and a half. When I get back each day, I have at least one, maybe three, strip ideas. I write them down while I’m walking and when I’m home I do one or two Zippy strips. And it’s a little like writing in my diary. Once in a while I sit there and I have no ideas…and that lasts for maybe 10 seconds. Zippy and the characters in the strip literally talk to me. Not in a schizophrenic way…and so I listen to that voice.”

Griffith says he will continue longer graphic pieces; next up for is a biography of Schlitzie Metz, one of the pinheads who appeared in Tod Browning’s 1932 film Freaks and an inspiration for Zippy. “I started researching Schlitzie and found two people who actually knew him well, his last manager—he worked in the circus right up to his death in 1971—and I found a man who had spent a summer with him in Toronto in a circus, living next door to him and kind of taking care of him, and I got wonderful stories. The idea is to make Schlitzie the Pinhead be a human being, not a sideshow freak, but to try to bring him to life as a human. I’m about 25 pages into it and will keep going. I have loads of material and am very grateful to have two very wonderful direct sources to use to bring it to life.”