Excerpted from The Comics Journal #186. April 1996

Kazimieras G. Prapuolenis — or the artist formally known as Kaz — first burst onto the comic culture scene in the late 1970s through his appearances in Art Spiegelman’s RAW (along with his School of Visual Arts classmates Drew Friedman and Mark Newgarden). Those early strips, an edgy mix of punk rock and classic comic aesthetics, served notice of the arrival of new voice that was both pioneering as well as grounded in the medium’s traditions. And like fellow RAW alumni Gary Panter (with whom he shares more than a few influences) and Charles Burns, Kaz’s style has evolved to where it is instantly recognizable — especially when it pops up in the work of other artists he’s “influenced.”

Born to Lithuanian immigrants in Hoboken, N.J. in 1959, Kaz has created an impressive and immense body of comic strip and illustration work through his apprearances in Weirdo, Bad News, the East Village Eye, The Village Voice, Details, Nickelodeon, The New Yorker, Swank, Eclipse, N.Y. Rocker, Screw, and Bridal Guide, along with many other comics, magazines and fanzines.

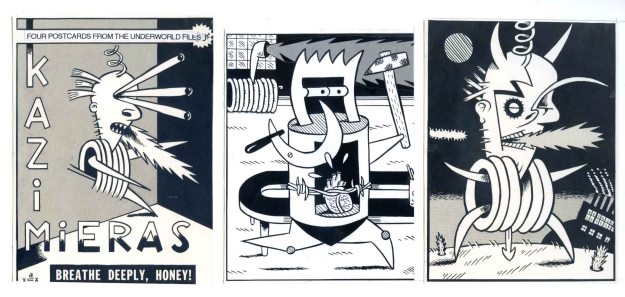

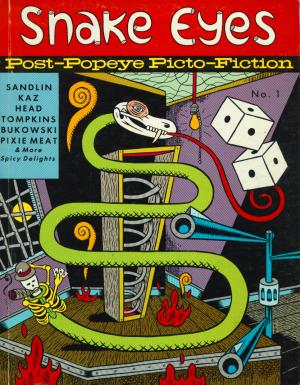

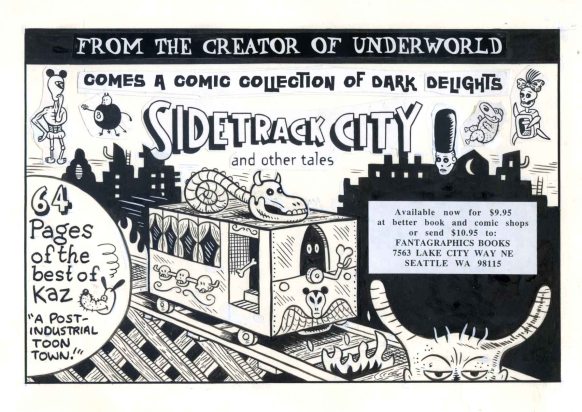

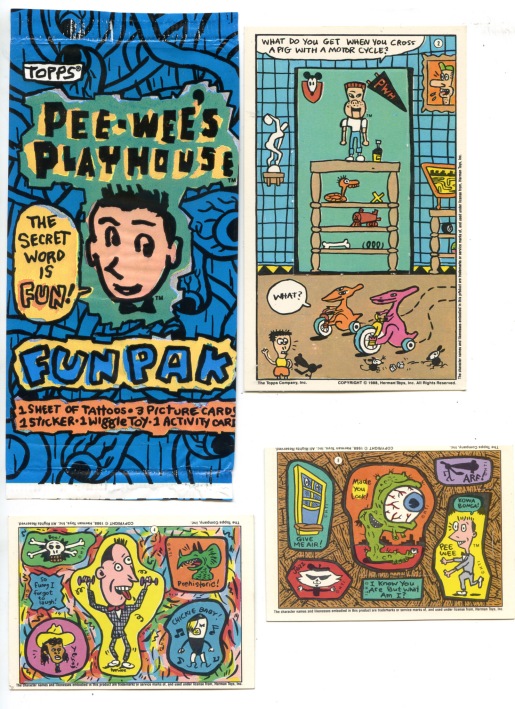

Since 1992 his weekly comic strip Underworld has appeared in alternative weekly newspapers across the country. Along with Glenn Head, he co-edited the comics anthology Snake Eyes, and has three collections of his work available from Fantagraphics: Buzzbomb, Underworld, and most recently, Sidetrack City. Other projects include the cover for writer Mark Leyner’s book My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist, various work for Topps Trading Cards and Pee-wee Herman Toy Designs, as well as several animation and Internet projects currently in the works.

Kaz lives in a pop culture-cluttered apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side along with his girlfriend, Linda Marotta, a book buyer for Shakespeare and Company and book reviewer for Fangoria magazine. The following is an excerpt from the interview appearing in TCJ #186.

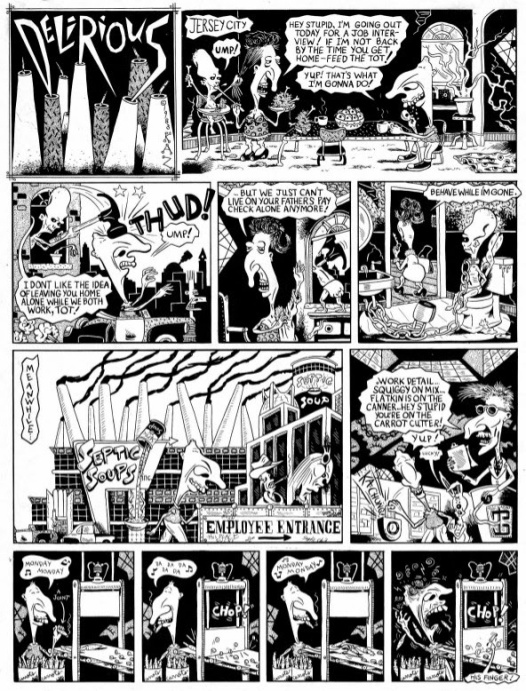

An early UNDERWORLD.

FACTORY JOBS

JOHN F. KELLY: Before we talk about your schooling as a cartoonist, do you have any opening statements?

KAZ: Underground comix made a man out of me.

KELLY: Did you go to art school right out of high school?

KAZ: No, I worked for a year or so.

KELLY: Doing what?

KAZ: I had a few factory jobs. The first job I had was at a plant called Springboard Records that had a license to press the Chipmunks’ albums. I swept the floor. That was my first job right out of high school. And it was completely disheartening to think that this was going to be my life. The forklift drivers felt so bad for me that they would lift me up on the forks of these vehicles that would rise up really high and deposit me up onto the top shelves of the warehouse where I would sleep all afternoon. I had a job working at a factory called Boyle-Midway that made Black Flag spray, and carpet cleaner, oven cleaner, that kind of stuff. It was an assembly line job. You would sit there next to the conveyor belt and watch the line in case a cap falls off a bottle. You’d have to put it back on. Or if a can had a leak, you’d toss it into the trash. The most dangerous spot on the line was right after the compression room where they forced the oven cleaner into the cans. Any one of those cans could blow up. One night I was sitting there with my dorky safety glasses on fantasizing about something when I heard a pop. I looked up and my whole face was drenched in oven cleaner. I felt my body being lifted up and then my head was shoved into a water fountain. A co-worker thought my eyes may have gotten sprayed. I also worked in an air conditioner factory. It was another mind-numbing assembly-line job. With an air-powered screw-gun, my job was to put in two screws that held the cooling unit into the air conditioner frame. That was it. All day long. The machines would come down the line non-stop. It was Modern Times. The place was big, hot, and noisy. I had some friends who worked there and they would drop Black Beauties and puncture holes into the compression tanks just to break up the monotony. One guy’s task was to line the cardboard boxes with plastic foam that had a sticky side on it. It would come off these gigantic rolls. One day he wrapped that foam around his head until he looked like a mummy and walked off the line. There he went, wandering throughout the whole factory in a daze. People were jumping out of his way. He finally made it to the nurse’s office where he declared, “My brain hurts!” He was fired on the spot.

KELLY: How long did you work there?

KAZ: About a year. I had my own breakdown. I disengaged from the machinery much like the main character in my strip, The Little Bastard. One morning I got a bit ahead of myself on the line when I stood back and watched the whole factory disappear. It was like at the end of an old cartoon where blackness engulfs the picture leaving a small circular view until the circle itself disappears. Then I blacked out. I woke up in an ambulance. I later learned from the hysterical Puerto Rican women who worked beside me that I fell down and started to thrash about banging my head on the conveyer belt. My screw gun, which was stuck in the “on” position, was flapping about on my crotch. No one wanted to touch me. They were convinced that I was a drug addict anyway, so they assumed I was having a freak-out! Later, the doctor at the hospital told me that I had some sort of seizure but they weren’t sure what it was. Two weeks later, I learned, the doctor blew his own brains out. I actually went back to work there. But it was so embarrassing. Everybody kept their distance waiting for me to freak out again. That’s when I decided to listen to my heart. I always toyed with the idea of being a cartoonist. And now it seemed if I didn’t try, I would die right there in the factory. So I quit and went to art school where the freak-outs were more pleasant.

KELLY: And this was in Hoboken.

KAZ: This is when I was living in Rahway, a suburb of New Jersey.

KELLY: When did your parents come to this country?

KAZ: My father came here in the early ’50s and my mother arrived in the late ’50s. He was responsible for getting my mom’s family over here, both being Lithuanian refugees. They had escaped Lithuania which had turned Communist. My father was a Lithuanian nationalist who was forced to fight for the Russians in WWII. The Baltic countries were a real mess at the time, what with the Germans and then the Communists stomping all over them. He had a lot of near misses and almost wound up being shot by a German firing squad. Or was that a Russian firing squad? It all sounds so confusing. I have this picture in my head of my father running around a battlefield like Charlie Chaplin being blown from one side to another. He was eventually approached by the CIA to spy on the Communists and he realized that if he took that job he would not be long for this world. There was an underground pipeline to America, so he took it. And all he ever wanted to be was a priest who worked in a leper colony.

KELLY: What did he do for a living when he got here?

KAZ: He worked in a factory. He had no other skill and he had no interest in improving his English. He also organized anti-Communist protests and taught Lithuanian classes to immigrant children and dreamed of one day returning to his beloved motherland. My mom was a housewife and then she worked in factories too.

KELLY: So you were born in Hoboken, NJ in ’59?

KAZ: I was born in 1959. I have a twin sister named Laima. We both have Lithuanian names. I also have two younger brothers, Vincent and Thomas.

KAZ as a TOT.

KELLY: What was it like growing up there?

KAZ: We were poor. Lived in a tenement building. Bought our clothes at the Salvation Army. Ate my mom’s horrible Lithuanian cooking. But we didn’t know any better. My dad had two jobs, so he was never around. We played on the streets, the city parks, abandoned buildings, the Hoboken piers. We were the Dead End Kids. There were always big family parties where the adults got drunk and the kids went insane. My favorite toy was an Alvin the Chipmunk bubble-bath container. But the Salvation Army also sold toys, so I always had a lot of junk. I watched a lot of kids shows and cartoons. I could see the Empire State Building from my bedroom window. Then, when I was ten, my parents had saved up enough money to put a down-payment on a house in Rahway, New Jersey, and off we moved to the suburbs. The people next door had a big yard with swing sets. I thought it was a public park so we played there until we were kicked out. It was my first taste of someone having something bigger and better than me. So instead of the Dead End Kids, we were now the Little Rascals. We played in the woods and built soap box derby cars and tree houses. But I always knew that my family was different. For instance we were forced to speak only Lithuanian in the house. My friends were convinced that it was a practical joke. As if we were speaking gibberish just to fuck with them. Nobody had ever heard of Lithuania, and I was beginning to doubt its existence myself. My father forced us to take Lithuanian classes at a Catholic parish in Elizabeth, NJ on Saturday mornings. Saturday mornings! I was deeply into television cartoons at the time. He had a hell of a time each week rounding us up for the car ride. We’d hide under the porch, up a tree, anything. And I couldn’t tell any of my friends about it. At these classes we would be forced to participate in Lithuanian folk dances. My brother and I would intentionally step on the other dancers’ feet just to get kicked out. I finally ran out of a class in a middle of a lesson one day and refused to return. Well, my father couldn’t do anything to get me back. He tried beating me. But one of my heroes at the time was Papillion, and I could take anything he dished out. Eventually I won and got to watch Scooby Doo to my heart’s content.

“HE’S AN ARTIST”

KELLY: What was high school like for you?

KAZ: Oh, it was miserable. Torture. I was a bad student. I had a hard time getting interested in lessons. I later learned that my high school was one of the worst in the state. I tried. I really tried to be normal. I even joined a baseball league at one point. But I hardly played at all because all my teammates were championship players, so I sat on the bench the whole time. I won two trophies, but I barely touched a ball. Just my own balls. I went through periods of joining clubs and other periods of being a total loner. Just staying home and watching television. Most of my pals were misfits. But I also dated and had girlfriends. Some kids thought I was cool because I could draw. They kept saying, “He’s an artist. He’s an artist.” Until I eventually became one. Though my grades were bad, I never thought I was stupid. I just didn’t give a shit. Four years of prison. Just counting the days.

KELLY: Did you start going into the city a lot when you were in high school?

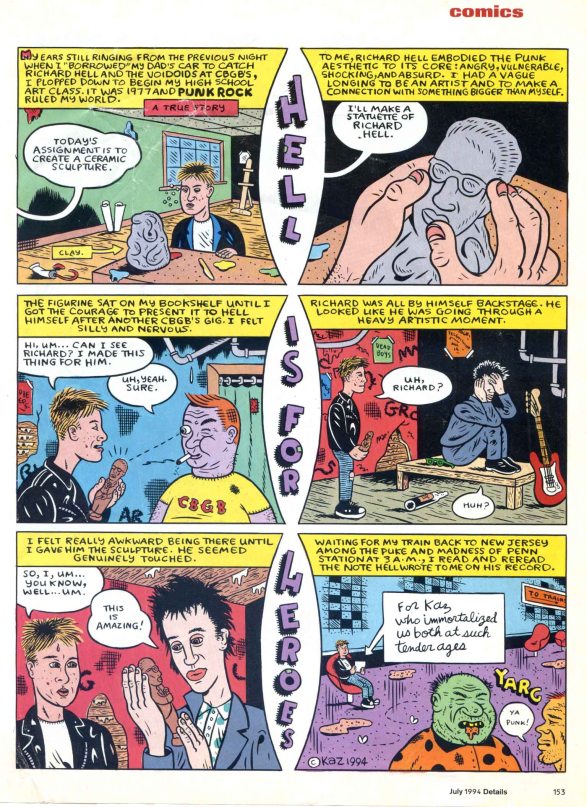

KAZ: When I discovered there was a train station in Rahway that was connected with New York City, I’d play hooky and explore the city. All the television stations that we got in New Jersey were broadcast from Manhattan. So we never knew what was going on in our own hometown, but we knew everything about New York. I felt like I lived there, anyway. When I found where CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City were, and that they would serve me liquor, I was there practically every week.

KELLY: So you were going to see bands and shows?

KAZ: It was the beginning of the punk scene — ’75, ’76. And I was completely into it. The Ramones, Blondie, Richard Hell. And then later the British punk bands. It was very exciting to a kid like me. I read all of the rock press. My friends were all into the leftover bands from the ’60s — Led Zep, the Stones, the Who. Although I liked those bands just fine, here was a new rock movement springing up practically in my backyard. I could not convince anyone to check out these bands with me. They sneered at me. As far as they were concerned, punk sucked and was for faggots. I alienated everyone. With my ripped jeans and leather jacket I stood out in sleepy Rahway town. People would scream, “Punk rock sucks!” at me as they drove by in their vans.

KAZ meets an early hero, Richard Hell.

KELLY: Were you reading Creem?

KAZ: I read Creem, I read Rock Scene, Circus… you don’t really read those magazine because there’s no real writing in them. You look at the pictures and you skim them.

KELLY: Were you drawing all the time?

KAZ: I started really drawing in junior high school. All through school, art class was my favorite. No rules. I got the best reinforcement in art. In junior high there was this kid, Bernard, who sat in front of me and drew these fantastically funny monsters. Big Daddy Roth monsters mostly. I wanted to emulate him and get some attention, too. Plus, it was more entertaining than doing math. He was good at drawing cars, too, and I was good at monsters so we would compare notes and crack each other up. I got real good at shading on a school desktop. Nice enamel surface. We’d leave these elaborate monster/car battle scenes for the janitor to clean off at the end of the day. Even then we would get upset when some other kid would cop one of our drawing licks: “Hey! You copied that from me, you thief!” Meanwhile I was copying everything out of MAD magazine!

KELLY: Nothing has changed.

KAZ: I was reading a lot of comics at this time, but I didn’t share my passion with anyone else.

KELLY: It was a secret?

KAZ: I didn’t hide it, but there was nobody in my immediate circle that read them. There were times when I didn’t have anybody to hang out with so I would just collect comics and read them off on my own. After a while, I became a comics junkie. I started to buy everything. I loved Spider-Man, Conan, and all those weird Kirby DC books like The New Gods and Forever People. I started sending away for back issues of Nick Fury Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., and Not Brand Ecch! I was soon scraping the bottom of the comics barrel buying Jimmy Olsen and Archie’s Madhouse Funnies. Any fuckin’ thing so that I wouldn’t have to live in reality. I started to draw my own homemade superhero comics, which were utterly pathetic.

KELLY: Well, look what you’re emulating.

KAZ: Then I discovered underground comics and everything changed.

KELLY: How did that happen?

KAZ: You know, after you start collecting enough comic books, you start running out, because they only come out once a month. You wind up with piles of the stuff and so you start reading the ads for a change. There were ads for back issues — you know, Golden Age and Silver Age books — so I sent for a catalog. In the back of one of these catalogs were ads for the underground comics I remembered seeing in a head shop once but was too young to buy. It took me a couple of months to get up the courage to send for some titles. I wrote that I was over 18 years of age and I felt like such a bad boy. I knew I was buying something nasty. Something worse than MAD or National Lampoon. Well, the first two books I got were Rubber Duck and a copy of Zap #3, the one with the S. Clay Wilson story of Captain Piss Gums and his Pervert Pirates. Well, it blew my little mind. Here were cartoon characters fucking, doing drugs and chopping each other’s dicks off! I hid them under a loose floorboard in the attic and quickly sent away for more. I wasn’t allowed to have MAD magazine in the house because my mom saw a back cover once that had a hippie crucified on a hypodermic needle and she said it was sacrilegious. And now I had Captain Piss Gums and Joe Blow!

I had already had a taste of this kind of stuff with National Lampoon. I loved their “Funny Pages” section. I was a big fan of Bobby London’s Dirty Duck. It’s not cool among my contemporary cartoonist pals to have liked Dirty Duck, but I thought it was hilarious. I also loved Vaughn Bodé, another no-no, the way he mapped out an entire universe from his mind. The mythology and space ships. It was all very unique and drenched in drug and hippie culture. It was Tolkien as an underground comic. Cheech Wizard was very funny. Cobalt 60 anticipated Heavy Metal comics and cyber-punk. And he was a true eccentric who cross-dressed and died accidentally during sex play. What’s not to like? This idea of creating your own private world has always fascinated me. That’s why I liked those Kirby books.

KELLY: I would buy those and just stare at them.

KAZ: Yeah, they look really good even today. They’re pretty amazing. All that demented machinery. His characters look like they’re made out of granite. They all wore expressions like they had permanent headaches. His writing was really blunt and at the same time mind-bending. Characters were constantly being hurled through time warps and dimensional trap-doors.

KELLY: When you were going into New York in high school, were you going to those comic book conventions?

KAZ: Oh, no. I didn’t even know they existed. I had no idea. The first time I ever went into a comic book shop it was a very weird experience. It kind of scared me. Because it was kind of dark and everything was in boxes. It smelled pretty bad in there. This was pre-Jim Hanley’s Universe and St. Mark’s Comics.

KELLY: I remember seeing my first comic shop when I was 10 and just being paralyzed by the sight of it. Anything you wanted was there, it was really traumatizing… When did you start going from imitating other artists’ styles to doing your own work?

KAZ: After my dismal failure trying to draw superhero comics I pretty much gave up drawing until I discovered the undergrounds. I would imitate Crumb’s comic book covers and I found that cartoony style more natural for me. I remember once copying a Mr. Natural cover with watercolors. My mom liked the Mr. Natural cover so much she hung it up on the living room wall. So that was very encouraging. Crumb’s work was very important to me because he drew in a style that I recognized from other comics but his stories were free from formula. They were truly shocking to me. And I met that challenge by drawing my own underground comic book called Bird Turd Funnies which I never finished. Crumb’s work is so organic and real I can’t say enough about it. Viva la Crumb!

Another important influence was a hard-bound edition of Krazy Kat comics that I sent away for. Again, here was a guy who had created his own universe with a deceptively simple drawing style. I felt like I could walk around in Coconino County and taste the ink. There was a photograph of George Herriman that I would stare at ’til I put myself in a trance. It’s a picture of him sitting at his drawing table with his hat cocked, dreaming about his comic. I would fantasize myself in his place sitting there in the newspaper office working on a cartooning deadline. Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy was another important influence for me. I would clip the Sunday strips and paste them into a scrapbook. Reading them over and over again, I was slowly teaching myself the mechanics of comic strip storytelling. In Penn Station, New York, there was a bookstore that had on one of their shelves a hardcover copy of The Celebrated Cases of Dick Tracy. It had no title on the front of the dust jacket. Just a drawing of Dick Tracy’s famous profile. Whenever my family and I would come back from a show or circus in New York City we’d wait for the local train home in that station and I would stare at that cover, too shy to ask anyone to pull it down for me. The thought of that big book containing nothing but Dick Tracy comics from the ’40s was driving me mad. I would stare at that cover until I was hypnotized. I finally saved the money to buy it and fell completely in love with it. It was dark, violent, and weird. drawn in a style that I could learn. You can still see Chester Gould’s influence in my drawing style.

KELLY: I think Dick Tracy is a big strip for a lot of people, although a lot of them wouldn’t admit it.

KAZ: They won’t admit it? Really? Dick Tracy is the seminal strip for cartoonists who draw detective/crime comics. There would be no Batman without Tracy and the grotesque criminals Chester Gould invented. Each panel is like a blueprint drawing taking you deeper and deeper into his dark, twisted Chicago cartoon gangland. I find his drawings to be like graphic noir. Sinister. I also collected the Crimestoppers Textbook panels.

KELLY: They always gave the best advice. I remember one that said you shouldn’t let people into your house to use the phone if you were an old woman. Did you read Nancy?

KAZ: Nancy I read without even thinking about it. Sometimes clipping them because the local paper ran them. It wasn’t until I went to the School of Visual Arts and took a class with Art Spiegelman and Jerry Moriarty who drew Jack Survives for RAW that I started looking at and reading Nancy a little closer. Moriarty had a very Zen-beatnik way of talking about Bushmiller that really clicked with me. Nancy soon became a celebrated strip among the RAW crowd. And whenever anyone would say it was stupid or they didn’t get it, we would just close our eyes and smile. Nancy was so corny it was beyond corny. It somehow shifted into the kind of meta-world that only Zen masters navigate.

KELLY: That was right before Bushmiller died.

KAZ: Right. [a moment of silence]

KELLY: So you weren’t studying Dondi, though.

KAZ: I read everything. I always loved Smoky Stover. Even when I was a kid. I remember reading it but not understanding it. I understood Spooky, the cat strip that ran at the bottom. Little Orphan Annie, when I was a kid, I remember had too many words and not enough action, although I remember liking Maw Green. Nobody talks about the influence of Harold Gray’s Maw Green on my work.

KELLY: I think Smoky Stover had a big impact on you.

KAZ: It sure did. But I didn’t think about it again until much later, when I started thinking about what kind of sensibility and style my hand was suitable for. There was that piece I did for Snake Eyes #3 called “Zak Smoke.” The look of that strip was intentionally goofy because the story itself was so dark and depressing. Zak catches a glimpse of his own impending death and then he runs from one death symbol smack into another until the strip ends with his enlightenment. The sign pops up like the corny puns that mushroom all over a Smokey Stover comic.

SVA

KELLY: What made you choose the School of Visual Arts in New York?

KAZ: I went there because somebody told me once that SVA was the School of Cartoon & Illustration, which I believe is what it used to be called. So I went there with a portfolio of drawings that I drew in high school. I actually had a strip that I did then called Mr. Roach, and my idea was that I was going to submit this to syndicates to get a daily comic strip. It was really bad. Badly written, badly drawn. It didn’t even have gags. But I did a few things right. I had six weeks’ worth. I learned about photostats. I paid for all the printing and I sent them out to all the syndicates and got rejections. I was sending copies of the strip to newspaper cartoonists looking for feedback. The only guy who wrote me back was Russell Myers, who draws Broom Hilda. He was very encouraging. His letter was written on green Broom Hilda stationary with a green envelope that had all of his characters frolicking about on it. It was very exciting to me at the time. I thought, “Maybe I can actually do this!” Although he did say that I should go to art school and learn how to draw.

KELLY: What did the syndicates say in their rejection letters?

KAZ: One of them said basically there was no way they’d ever print a strip about a cockroach [laughs], so right away I was doing the underground comic thing. I still love that daily comics form. But my sensibilities and humor are more in tune with the underground. The writing in Underworld is all over the place. One week it’s R-rated, the next week it’s a G.

From Robert Crumb’s WEIRDO, 1984.

KELLY: Well, I think the strip is such a traditional strip; I mean, it’s black and all….

KAZ: Right. And the gags revolve around heroin, death, and mutilation.

KELLY: But if you change a couple of words around, it looks like a classic.

KAZ: That’s the way I designed it. To getcha. To make it look appealing.

KELLY: What did you submit to get into SVA?

KAZ: Stuff from high school. I literally sat down and did a drawing specifically to submit.

KELLY: Seconds after it was done?

KAZ: On the train! They must have been desperate for admissions, because those drawings were pretty awful. From what I understand, it wasn’t that difficult to get in at that time. I don’t know what it’s like now. I went with the thought of getting into animation. But they expose you to everything: painting, sculpture, photography. My head was swimming with the possibilities. The more I thought about animation, the less I wanted to do it. I took Art Spiegelman’s cartooning class. Only after I had signed up did I go back to my underground comics collections and pullout a bunch of his strips. Although I did remember the story that Maus came from in the Funny Animals book. I remember reading that strip over and over again. It was a very powerful story. Then after I took his class I went back and I looked up all the back issues of Arcade and I got a copy of Breakdowns and I really appreciated where he was coming from. He was very dry and arty, He was so passionate about the possibilities of comics that I got sucked in allover again.

KELLY: Was that when you met Mark Newgarden and Drew Friedman?

KAZ: I met Mark and Drew in Harvey Kurtzman’s class. Harvey’s first class assignment was that we had to pair off and do cartoon self-portraits. I drew Mark and he drew me. He drew me as a cartoon punk from new Jersey. I was wearing a black leather jacket, spiky hair, purple jeans. I thought punk was cartoony to begin with. And that attitude eventually encompassed everything: the visual arts, writing. It was starting to affect the arts at the time. This was ’79, ’80.

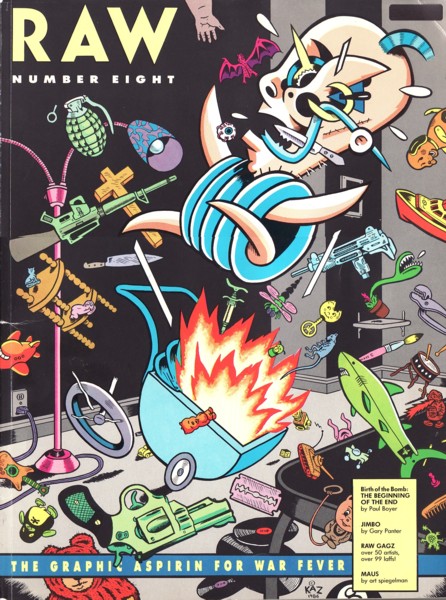

RAW #8, 1986 with a cover by KAZ.

KELLY: So you show up at SVA with spiky hair and you meet up with Drew Friedman and Newgarden. What did you think of each other?

KAZ: We were friends at first. I’m not sure what they thought of me. Mark and Drew and a few others were kinda cliquey. Drew seemed pretty self-absorbed, always cracking jokes. Mark was the same, joking and laughing during class. We didn’t socialize. I remember when Spiegelman started RAW, he called Drew, Mark and myself after class and asked us to contribute some comics. He said he wanted some experimental student work. I was looking for people to relate to. I was into the whole idea of scenes. I was reading about the surrealists and they had a scene. The punk rock thing was a scene. I was looking for a cartoon scene but it didn’t really happen until a bit later with Bad News and Snake Eyes. And even then it wasn’t much of anything. It’s hard to keep people together in New York. There’s too many distractions. So Spiegelman started this workshop class after his lecture class. He hand-selected a few students for it and that was fantastic. I learned so much in that class. Art was the best teacher I’ve ever had. I don’t know how he felt about me at the time. I remember him calling me a snot once.

KELLY: That’s just about what he said on the back of your new book. But you’re funny, which is what saves you.

KAZ: I wasn’t trying to be funny then. I was trying to do art comics. I was into Krazy Kat and all this avant-garde stuff. So I was gonna be the guy who would experiment with page design and layout. Trying to incorporate the narrative into strange page designs. In my second year at SVA, I already had a regular comic strip being published in The New York Rocker.

KELLY: And it had a punk feel to it.

KAZ: I guess it did. But I always thought comics did, anyway. I mean, The Yellow Kid had a punk feel to it, Barney Google, Snuffy Smith…I mean, Snuffy Smith was like a hillbilly punk. He was lazy, you know, shooting people, drinking moonshine.

KELLY: There’s a lot of proto-slackers in the history of comics: Jughead, Wimpy; Sluggo, and all those hillbillies.

KAZ: Maybe cartoonists admired those types because it’s a lot of work drawing cartoons so you wish you could slack off.

KELLY: What was the Kurtzman class like?

KAZ: It was a complete waste of time. Unfortunately, he wasn’t teaching what he was good at, which was comics. But for some reason, he was teaching gag cartoons. It was a silly class. He would come in and he’d say, “Okay, today we are going to practice WORD BALLOONS!” Or cartoon sound effects. So we’d sit there going KARANG AND BADOOM and POW. It was really stupid. Here’s this master who created MAD and Two-Fisted Tales completely wasting his and our time. Friedman and Newgarden were real palsy-walsy with him, trying to upstage him with silly sounds and whatnot, so sometimes nothing would ever get done.

KELLY: They were palsy-walsy with him after they made him cry.

KAZ: The story I remember about that day was Kurtzman was showing some slides and Friedman and some clowns were in the back making Three Stooges noises. All I could think about was that he’d been working all day trying to sell some piece of shit cartoon to Hugh Hefner, driving all the way down from Connecticut to teach this useless art class to a room of students that couldn’t give a shit, and all we had to offer him was, “Hey, Moe!” and “Nyuck, nyuck!” Making wise cracks at everything he said. He looked tired. Real tired. He finally bowed his head and turned on the lights and walked out of the classroom. Leaving us there in stunned silence. Then he comes back in and goes into a sad speech about how he doesn’t have to do this to make a living blah, blah, blah. It was sad and pathetic. Everyone was nice to him after that, but it was too late.

KELLY: What types of things would Spiegelman focus on?

KAZ: He ran the gamut. He would talk about everything from the story-telling to the actual words that the cartoonists would use, like the way Herriman would use dialect. He gave you the whole scope of it. He talked about inking styles a bit, but Spiegelman isn’t really a techno-nerd the way a lot of cartoonists are. It was theoretical. He had an intellectual approach that I found refreshing. I never heard comics discussed that way. He made you want to do smart comics. There was nothing else you could do. You had to do comics that reflected your intelligence and knowledge of art and literature. Aspire to greater heights. At least that’s what I got out of it. I found myself going through the whole history of comic approaches and trying them on for a while.

STYLE

KELLY: In Buzzbomb, I can identify several different phases of your work. the post-psychedelic stuff; etc. The Tot story seems to stick out as most like what you are doing now, maybe a little darker.

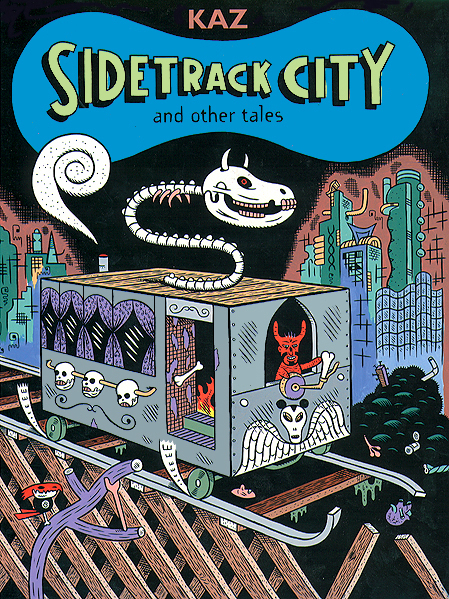

KAZ: With that work, I was moving away from comics as pure design and I was trying to tell a tale. I found that people remembered characters and stories more than they remembered style. Very few people come up to me to compliment me on my layout or style. They remember something a character said or did. So I taught myself how to tell a story. After dropping out of art school, I moved back into Hoboken and wasn’t doing much of anything except taking two months to draw a page of comics. I would draw and re-draw panels like a lunatic. Peter Bagge was living in Hoboken at this time, and we would visit each other occasionally. We’d met before when I submitted a comic strip to a publication he was editing at the time called Comical Funnies. At this time, he was working on STOP! with John Holmstrom, JD King, and Ken Weiner. I got to know the whole gang and they would tease me for being in RAW. Apparently, they all tried to get into RAW, but were rejected or something, so they all hated Spiegelman. They literally saw themselves as the antithesis of RAW. Funny, disposable, lightweight. I liked the idea of a purely funny comic book so I submitted some comics. But I always felt they were suspicious of me. You know, I was one of the RAW guys. Peter and his wife Joanne would often throw these drunken dinner parties back then. Everybody was drawing for SCREW. They were a fun bunch of characters. After I did Buzzbomb I. had decided I didn’t want to draw comics anymore. I was just getting nowhere with it. Underground/alternative; publications pay $50 a page, and I just wasn’t making any money. So I started doing illustration work, and that started taking up a lot of my time. But still there was this nagging feeling that I had to express myself with comics, so I started working on a comic strip in secret. I didn’t talk about it to anybody. I didn’t think I was ever going to finish it, and I didn’t ever know what the story was going to be. I just started it and it wound up being Sidetrack City. It pushed me right back into comics. I was going through a real tumultuous time in my life. I had broken up a relationship of seven years, I moved into an apartment with a friend of mine–Alex Ross, who’s a painter–and getting into psychedelic drugs, and reading books on philosophy, just living this complete bohemian, intellectual art life. And all that spirit and energy went into Sidetrack City. At the same time I was doing a lot of illustration work, I was doing Pee-Wee Hennan designs with Gary Panter, comics for National Lampoon, which got me to exercise my funny bone. I remember Drew Friedman giving me that job saying, “Just do a page. The only thing is, it has to be funny.”

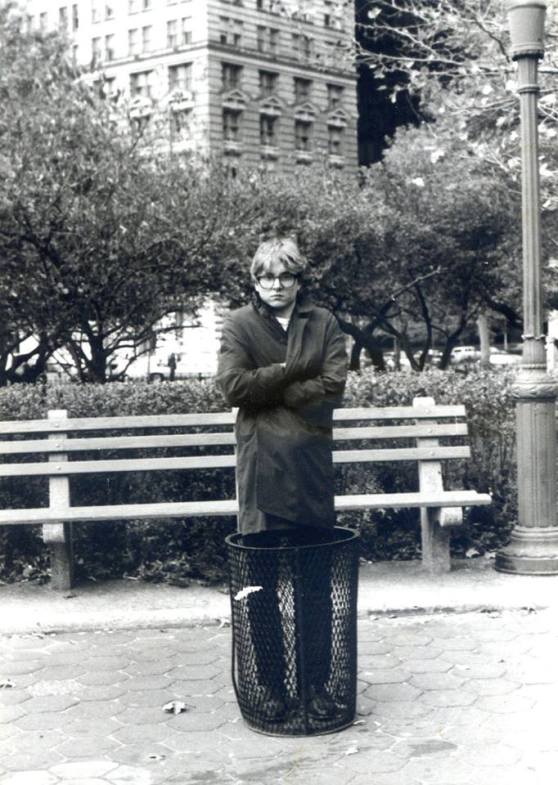

Kaz’s old studio in New York City at 109th Street and Broadway in a photo taken in the mid-1990s, around the time of this interview was conducted.

KELLY: It seems like that period had a big effect on your current style.

KAZ: Because I was cranking out more comics, I had to reach deeper into my skull for ideas. Anything that seeped out, I used. In the past I would usually approach a strip as if I was doing something important. I wanted the work to be arty. Pretentious was not a dirty word to me. But now I had more deadlines and funnier stuff slipped out. I was staying up, working later and later. All those old gag comics began to look tragic to me. One morning I woke up and everything in my room and apartment had a black outline around it, with crosshatching and color separation. I had gotten cartoonal knowledge! I learned to relax and allow my drawings to get cruder so that my comics could get more organic. Closer to the way my brain worked. Glenn Head was starting up the old Bad News comic book, which became Snake Eyes. And I was excited to get involved with that, because there were a lot of talented cartoonists living in New York that did not have a regular outlet. I envisioned a book that showcased the New York style of cartooning that had come out of SVA and RAW.

Snake Eyes, #1

KELLY: What was it like working with a co-editor?

KAZ: It was fun to sit around and plan the books and talk about comics. We had a similar vision about comics. We both love that gritty urban wiseguy school of cartooning. For me, the most rewarding aspect was contracting artists whose work I admired and asking them to draw a few pages. My hands would tremble as I opened the envelopes. Since we weren’t paying much and didn’t really crack the whip as far as deadlines went, the issues took forever to put together. Some of the strips were too weird for most people; Jonathon Rosen, Jayr Pulga, and Brad Johnson–their visions seemed too private for most readers. At first, I had a hard time convincing Glenn to run Brad Johnson’s work.

KELLY: It looks like it’s drawn by a retarded 12-year-old. Which is why I like it.

KAZ: To be fair, Glenn tried to get me excited about certain cartoonists that I couldn’t see until much later. Dan Clowes is one example. At first I thought he was too slick and surface-oriented. But I was wrong. Now he’s one of my favorite cartoonists. And he’s doing work with so much depth, it’s astonishing. Now I see people on the streets and I automatically think, He’s a Clowes character!” I wasn’t looking below the surface. But for the most part, Glenn and I agreed. It’s just that we don’t seem to have any commercial instincts. I tend to gravitate to work that looks wrong. I can remember Alex Ross and myself trying to draw like someone who was insane or retarded. Instead of attempting, like everybody else, to be really sophisticated or smart, we got into this idea of American dumbness, like Philip Guston, whose work looks completely dumb on the surface -big eyeballed guys, big giant feet -but there’s a sensitivity there. Basically, he was still doing Abstract Expressionist painting, but he was using these really simple symbols that looked wrong on the surface, like Mutt and Jeff. Philip Guston was called a stumblebum painter by a critic once. Captain Beefheart sounds like Guston paints. I think it’s a way of being nostalgic for the things you liked as a kid, like Popeye, but also being sophisticated at the same time. That’s sort of what I do with Underworld. Some of the gags are really dumb, but they make me laugh so I leave them in. If it wasn’t a weekly strip, I’d be a little more thoughtful. But because I have to put it out every week, parts of my personality that would otherwise be guarded pop out. So you see me as the dumb vaudevillian guy, falling down for a laugh.

KELLY: So Snake Eyes is no more?

KAZ: It was too difficult editing a comic book and balancing an illustration career and doing my own comics and having a social life. I was also co-hosting a weekly radio show. Glenn Head did a wonderful job on that book, but it was driving him batty too. Fantagraphics was not paying us anything for editing and designing it. We were only getting a page rate. And it didn’t seem like anyone besides our fellow cartoonists were interested in an anthology comic book with no theme that only came out once a year. It kicked the shit out of us after three issues.

OTHER INFLUENCES

KELLY: I want to ask you about the influence of psychedelics on your work, since you’re currently on a natural amphetamine…

KAZ: Ginseng.

KELLY: When did you first start doing drugs?

KAZ: [laughs hysterically] It depends on the drug. I drank beer and smoked pot in high school like everybody else.

KELLY: I can’t imagine drawing on pot.

KAZ: I’ve inked on pot. Then the next morning I would see that I’d done these elaborate cross-hatching jobs that would go on forever and there would be thousands of little characters in the background. It was too much. Plus the idea was a lot worse than you had imagined it when you were high. Some people can do it. As far as other influences, I’m not sure that psychedelic drugs are a direct influence in the way my work looks. I think there’s a difference in the type of story that I might approach. Psychedelics put your head in a place that allows you to look at things differently. It’s not necessarily the right way, but it’s different and that’s what I’m after. It could be a dangerous thing playing with your consciousness. Your concept of the world changes. It becomes organic and infinite. I never did much drawing on hallucinogens. My hands were too shaky and my mind was exploding with visions. I jotted down ideas. Lot’s of ideas. STRANGE ideas.

KELLY: Do acid and mushrooms affect you differently?

KAZ: They sure do. Mushrooms to me are more physical. Your body feels more rubbery. And the mushroom make you want to lie down. The mushroom peak has a shorter duration. But the visions are just as intense. At first geometric shapes evolve into full-blown hallucinations. Whereas LSD gives me a more high-tech feeling. The world machine grinding away.

KELLY: Can you draw though?

KAZ: I was once staring at a piece of paper and seeing the most amazing things. But when I put pencil to paper to try to draw what I was seeing, the visions would quickly mutate. I found myself chasing these elusive images. You wind up in places that you wouldn’t normally go. Down a rabbit hole.

SIDETRACK CITY, 199x?

KELLY: You see it as affecting your storytelling, but in Sidetrack City, the overload of images seems like you’re recreating a trip.

KAZ: Well, it was an inner and outer journey for the main character. The landscape and the architecture had to reflect Bizmark’s inner life. So in that sense, it was very psychedelic. There was the sense of being lost and pushed around by sinister forces that recreated the deep paranoia that can accompany a psychedelic trip. Schizophrenic delusions and a sense of reality being only a shabby backdrop to the real reality happening behind the curtain. At the same time, there’s the magic. The knowledge that you create your own story. I wanted it to be emotional. The drawings had to be fun to look at. Lots of inventive backgrounds and playful layouts. You can tell what I was looking at. I didn’t care if the drawings looked like someone else’s or if the characters were in proportion. What mattered was how I was feeling at the time. Cartoonists always play this game of accusing others of stealing styles. It’s the guys who assimilate styles that learn and move on the quickest. At one point, your own hand will come out and by then you will have had all this experience. Then anything you draw will look like your own. You can recreate the whole world in your own hand. Now that’s psychedelic.

Original art for an ad for KAZ’s Sidetrack City, 1996. The strip originally appeared in Snake Eyes, #2, 1992.

KELLY: So how often do you do drugs now?

KAZ: I’m tripping right now. [laughs]

KELLY: Drinking certainly has a long and venerable tradition in the world of cartooning.

KAZ: It’s a pain killer.

KELLY: The thought of drawing Bazooka Joe for a living could be unbearable.

KAZ: Bazooka Junkie Joe.

KELLY: Do you see a difference between your art pre- and post-psychedelics?

KAZ: Yeah, but growing up in the ’7Os meant that you swam in the cultura1 debris of the ’60s which was left over psychedelia. Trippy black light posters, underground comics and Peter Max 7-UP ads. More than create that kind of world for me, the psychedelics allowed me to understand it.

KELLY: What is your process for working on a weekly strip?

KAZ: I’ve got a couple of things I do. One is if I have the time, I’ll sit down and work in my sketchbook. I’ll draw a panel, create a character and stare at it until I imagine what happens next. I wind up with a lot of three-panel strips with no punch lines. I just leave it alone and then weeks later I’ll re-read it and come up with an ending. Or if I have a good idea, I’11 riff on it, so that I’ve got a little series of ideas going. Quite often, I will sit down the day before and just bang something out.

PATCHES ON EVERYTHING

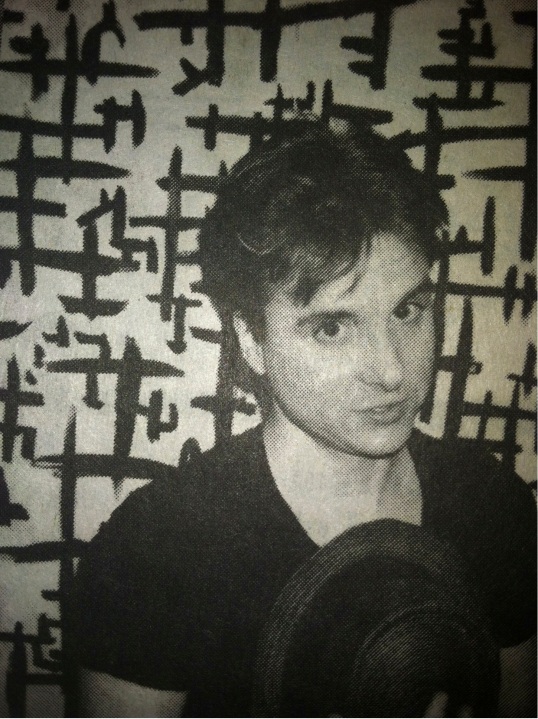

KAZ in the mid-1990s.

KELLY: Have you thought about what it would take to do a daily strip?

KAZ: Yes. A lot of money and a crew of assistants.

KELLY: The whole concept of “underground” is totally bizarre at this point. Stuff that was underground 10 years ago is mainstream now. Everything from music to magazines and fashion.

KAZ: But the extremes are still hard to put over on the general public. For instance you don’t hear many groups that were influenced by Captain Beefheart being played on the radio. You never hear Frank Zappa on the radio. There are examples of success stories of great weird stuff, Tim Burton, The Simpsons. So it’s part of the evolutionary art process. Someone takes a chance with something really weird or you have a visionary artist with a small audience and somebody else takes a piece of it with a much broader appeal and that becomes successful. Primus reminds me a little of Zappa but more homogenized. Life in Hell has the attitude of an underground comic. But it’s written more professionally and it’s easier to look at.

KELLY: If you got the opportunity to do a daily strip on your own terms, would you do it?

KAZ: Yes. It would probably kill me, but if it were on my own terms I know it would be a success. People would be shitting in their pants while reading it.

KELLY: What if you had to just tone it down slightly?

KAZ: Meaning I would have to get rid of the hypodermic needles? I could do that.

KELLY: What if you had to tone it down completely but you were going to be paid a lot of money?

KAZ: Well, why would they bother asking me to do it at that point?

KELLY: Do you have any favorite source material?

KAZ: Sometimes I look through old comic strip collections. I don’t get specific ideas, just little random nudges. In Underworld, a lot of the pieces hearken back to things that look familiar, like the arms and the heads. I sample old bits that I find funny looking. My other comics style is meant more to be creepy looking than funny. Now I’m beginning to think that Sad Sack is a long-neglected American classic.

KELLY: Beloved by millions. I can see the Sad Sack influence in some of your earlier stuff, the folded over noses and the eyes.

KAZ: Total lids. Gary Panter does a character called Henry Web who kind of looks like Sad Sack, too. It’s getting back to the Mutt and Jeff thing. The bad, grungie drawing style. These low-rent American characters, scheming for a living. There’s poetry there. I grew up in a tenement building in Hoboken. Now I live in a tenement building on the Upper West Side. I watched The Honeymooners. I have an affinity for the bluesy, trash can, bare light bulb, scratch-a-funny-face-on-a-Chinese-menu style of cartooning.

KELLY: There’s so much despair in that stuff.

KAZ: The Salvation Army School of Cartooning. Dirty sinks, loose floorboards, cigar butts, a half a bottle of beer . I dunno…. Nasty pin-ups, scratchy records, and dust everywhere. Patches on everything. Blankets, couches, dogs, foreheads!

KELLY: I kind of cringe even asking this. but what do you think of post-modernism?

KAZ: I think it’s a beautiful thing, man. [laughs] No, really, modernism just ran out of steam and had to double back on itself. In fact, I think one of the first post-modernists was Harvey Kurtzman with MAD. I’m convinced that he influenced all these painters. They all read MAD when they were kids. So David Salle grows up and puts Tex Avery cartoons next to a pornographic image and blows everybody’s mind. I do it, too. Mixing old-fashioned animation, newspaper cartoons and underground comics. Twisting it, finding my own voice in that. It’s tough in comics because you have to draw figures and have them walk around in landscapes. If you make the thing look too original readers will lose their bearings. For somebody like Mark Beyer, who’s a complete and total original, sometimes he’s difficult for people to read because he’s coming straight out of his own head. There are no sign-posts. As a matter of fact, one road out of post-modernism is outsider art. We’re now moving into post-outsider.

KELLY: It’s interesting that you, Newgarden and Friedman all studied with Kurtzman during a period of your artistic development and today your work all comments on the history of comics and entertainment–either in content or style–as much as anyone’s. Yet, without exception, you all say he was a terrible teacher. You’d think there would be more of a natural link between his work and yours.

KAZ: By the time we had him, Kurtzman’s ideas had already been assimilated into the culture. It was probably more Spiegelman’s “Language of the Comics” lecture course that sparked ideas. When you’re a student, when you’re young, you’re stepping into other people’s ideas and feeling what it’s like. We had assignments to draw a comic strip like so-and-so or take a page from a novel and draw it as a comic strip. Then again, Drew Friedman walked in with a stippling style and walked out with the same stippling style. I used to see his graffiti in the school bathrooms where he used a more traditional cartooning style. Stippling on the toilet was too time consuming perhaps?

PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE

KELLY: Do you ever go back and look at your old stuff?

KAZ: Sometimes. I’m not embarrassed by it, except for the grammar and misspellings. But that was just me, where I was at the time.

KELLY: I notice you sometimes re-use characters from older stories.

KAZ: One of the hardest and most rewarding things is designing a new character. And there are some characters I just love drawing. That’s why I did so many Tot stories. I just loved drawing that head. Same with Little Bastard.

KELLY: The main thing I think of when I see your work is that it’s really its own unique universe. You’ve really created your own world. Is that all the same world even in different stories?

KAZ: A lot of the stories take place in Sidetrack City. One of the reasons I create my own world is because I was never very big on going out into the street and sketching. I do it when I have to. Even when I use photo references I change them considerably. Basically, I’m dissatisfied with how the world looks. Nature is perfect, but cities and houses could be more interesting. Why not live in a house that looks like a big baby’s head? Why don’t corporations look more evil than they do now? Instead of water fountains in front of their buildings, why not flames?

KELLY: Who are some cartoonists that everybody might not have seen that you think are doing good work?

KAZ: Right now I’m working on a comic strip with Timothy Georgarakis for Zero Zero called Meat Box. I’m writing and doing Breakdowns and he is drawing, inking and lettering. His drawings are amazing. Weird, funny, inventive. I really like Ted Stern’s work. Chris Ware is great. He’s like some mutation of a golden age cartoonist and Sam Beckett. Dan Clowes continues to do strong personal work. Tony Millionaire who draws Maakies for the New York Press does real nice work. He’s a big cartoon character himself. I watched him fuck a slice of pizza in a bar the other night. And then there are the cartoonists whose work I’ve always liked: Gary Panter, Mark Beyer, Charles Bums, Brad Johnson, Krystine Kryttre, Mark Newgarden. There was this weird guy from Texas, A.C. Samish; who would draw dominatrixes and steam engines.

KELLY: The first time I met you, I knew you as much from your cartoon work as for your radio show on WFMU. [A free-form radio station in East Orange, New Jersey.]

KAZ: Yes, The Nightmare Lounge with my co-host Christ T. Playing punk, art damage, hillbilly blues, noise, space-age bachelor pad music. We’d get drunk and take on-air phone calls. We interviewed Peter Bagge, Robert Williams, Gary Panter , Mark Newgarden, Joe Coleman, the Friedman brothers. I did it for a couple of years. After a while, I felt that I was spending too much time playing other people’s art work when I should be home drawing.

KAZ artwork for the TOPPS produced PEE WEE’S FUNHOUSE FUN PAK products, 1988. Art direction by MARK NEWGARDEN.

KELLY: What direction do you see your comics going in now?

KAZ: I’ m trying to decide if I should take the plunge and do a solo quarterly comic book or if I should continue to push the weekly comic strip. I’m also planning out a graphic novel. I’d love to design and write an animated cartoon. I’m even drawing comics for children in Nickelodeon magazine. “Just don’t make it scary!” the editors keep telling me. It’s not the kids who freak out–it’s the neurotic, parents. I used to read Captain Pisspants and His Pervert Pirates, and look at me.